ASAVARI See ASA ASCETICISM, derived from the Greek word askesis, connotes the `training` or `exercise` of the body and the mind. Asceticism or ascetic practices belong to the domain of religious culture, and fasts, pilgrimages, ablutions, purificatory rituals, vigils, abstinence from certain foods and drinks, primitive and strange dress, nudity, uncut hair, tonsure. shaving the head, circumcision, cavedwelling, silence, meditation, vegetarianism, celibacy, virginity, inflicting pain upon oneself by whips and chains, mutilation, begging alms, owning no wealth or possessions, forbearance and patience, equanimity or impartiality towards friends and foes, eradication of desires and passions, treating the body as something evil or treating human life as a means of achieving ultimate release or union with God all these are subsumed under ascetic practices. The history of Indian religiousness presents the ultimate in the development of the theory and practice of asceticism.

Evidence of the existence of ascetic practices in India has come down to us from the most ancient period of known history; archaeology and literature have documented its growth as a panIndian religious phenomenon; all the systems of religious thought that have ever appeared on the soil of India have been influenced in varying degrees by the philosophy and terminology of asceticism. Ancient Indian literature abounds in ascetic terminology and there are numerous terms which refer to ascetics or to diverse ascetic practices. Muni, yati, bhiksu, yogin, sramana, tapasvin, tapas, mundaka, parivrajaka, dhyanin, sannyasin, tyagin, vairagin, atita, udasina, avadhuta, digambara, etc. are terms frequently used in Indian religious tradition. Nontheistic systems such asJainism, Buddhism and SankhyaYoga provide instances of ascetic culture in its.

classical form. All these Sramanic systems of faith are predominantly ascetic though their philosophical theories place varying degrees of emphasis on bodily askesis. Forms of asceticism differ inJainism and Buddhism, the former being an extreme instance of it. Asceticism is the heart ofJaina caritra or acara which, along withJnana and darsana, constitutes the way to moksa. In the Buddhist form of asceticism, there is no metaphysical dualism of God and the world, or of soul and the body. Phenomenal existence is viewed as characterized by suffering, impermanence and notself.

The aim of ascetic culture is to go beyond this sphere of conditioned phenomena. The keynote of Buddhist ascetic culture is moderation; self mortification is rejected altogether; tapas is a form of excess which increases dukkha. The aim of ascetic effort is to secure freedom from suffering; this ascetic effort is to be made within the framework of the Middle Way. Among all schools of Indian ascetics the guru or preceptor is held in the highest esteem. No one becomes an ascetic without receiving formal initiation (diksa) or ordination (pravargya) at the hands of a recognized teacher who is himself an ascetic of standing.

Practice of various kinds of physical postures (asanas), meditation, study of Scriptures, devotional worship, discussion on subjects of religious and philosophical importance, going on pilgrimage to holy places, giving instruction to the laity, accepting gifts of dress materials and foodstuff, and radiating good will and a sense of religiousness and piety, are the usual facets of the life of Indian ascetics. Ascetic way of life, in any religion is the way of self mortification. Injury to others is however disallowed. But Sikhism which of course emphasizes the importance of nonviolence never lets this dogma to humiliate man as a man and accepts the use of force as the last resort. Says Guru Gobind Singh in the Zafarnamah : chu kar az hamah hilte dar guzasht/halal astu burdan ba shamshir dast (22).

Sikhism denies the efficacy of all that is external or merely ritualistic. Ritualism which may be held to be a strong pillar of asceticism has been held as entirely alien to true religion. Sikhism which may be described as pravrtti marga (way of active activity) over against nivrtti marga (way of passive activity or renunciation) enjoins man to be of the world, but not worldly. Nonresponsible life under the pretext of ascetic garb is rejected by the Gurus and so is renunciation which takes one away to solitary or itinerant life totally devoid of social engagement. Says Guru Nanak: “He who sings songs about God without understanding them; who converts his house into a mosque in order to satisfy his hunger; who being unemployed has his ears pierced (so that he can beg); who becomes a faqir and abandons his caste; who is called a guru or pir but goes around begging never fall at the feet of such a person.

He who eats what he has earned by his own labour and yet gives some (to others) Nanak, it is he who knows the true way” (GG, 1245). Here one may find the rejection of asceticism and affirmation of disciplined worldliness. A very significant body of the fundamental teachings of the Gurus commends nonattachment, but not asceticism or monasticism. The necessity of controlling the mind and subduing one`s egoity is repeatedly taught. All the virtues such as contentment (santokh), patience (dhiraja), mercy (daya), service (seva), liberality (dana), cleanliness (snana), forgiveness (ksama), humility (namrata), nonattachment (vairagya), and renunciation (tiaga), are fundamental constituents of the Sikh religion and ethics.

On the other hand, all the major vices or evils that overpower human beings and ruin their religious life, such as anger (krodha), egoism (aharikara), avarice (lobha), lust (kama), infatuation (moha), sinful acts (papa), pride (man), doubt (dim`dha), ownership (mamata), hatred (vair), and hostility (virodh) are condemned. Man is exhorted to eradicate them but certainly not through ascetic self mortification. Sahaj is attained through tensionfree, ethical living, grounded in spirituality. In Sikhism all forms of asceticism are disapproved and external or physical austerities, devoid of devotion to God, are declared futile. An ascetic sage who is liberated from all evil passions is called avadhuta in Indian sacred literature.

Guru Nanak reorientates the concept of avadhuta in purely spiritual terms as against its formularies. The sign of an avadhuta is that “in the midst of aspirations he dwells bereft of aspirations” suni machhindra audhu nisani/asa mahi nirasu valae/nihachau Nanak karate pae” (GG, 877). An ascetic is defined again as “one who burns up his egoity, and whose alms consist in enduring hardships of life and in purifying his mind and soul. He who only washes his body is a hypocrite” (GG, 952).

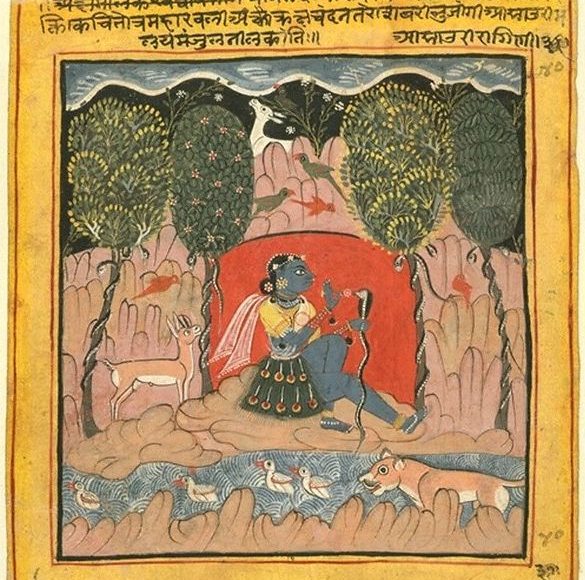

Asavari in Sikhism: A Melodic Pathway to Spiritual Elevation

Asavari is one of the ancient ragas in the Indian classical music tradition, and it holds a significant place in the Sikh musical framework, which is deeply intertwined with spirituality and divine connection. Ragas, including Asavari, are not merely artistic expressions in Sikhism—they serve as vehicles for conveying the profound messages of the Gurus, helping to elevate the listener’s soul and foster a connection with the divine.

Understanding Asavari

Asavari is a raga that evokes emotions of introspection, tranquility, and humility. Its essence is meditative, making it a fitting medium for expressing spiritual longing and the path to self-realization. Asavari creates an atmosphere where the soul can resonate with the eternal truths of life.

In classical music, Asavari is typically performed during the daytime and is characterized by its pentatonic (five-note) composition and descending melodic movements. In Sikhism, this raga is used to enhance the depth and understanding of the Guru’s hymns (Gurbani), imbuing the verses with emotional resonance that transcends the physical plane.

Asavari in Gurbani

The Sikh Gurus integrated various ragas, including Asavari, into the sacred Guru Granth Sahib—the spiritual scripture of Sikhism. These ragas were meticulously chosen by the Gurus to accompany their hymns, ensuring that the music and lyrics together conveyed the intended spiritual and emotional depth.

Asavari is employed to express themes of humility, surrender, and the longing for divine grace. Through this raga, the Gurus remind Sikhs of the transient nature of the material world and encourage them to focus on their spiritual journey.

Spiritual Significance

The inclusion of Asavari in Sikhism exemplifies the unique way in which music serves as a spiritual tool. It highlights the philosophy that devotion is not confined to rituals alone but can be expressed through heartfelt emotion, creativity, and introspection. The meditative quality of Asavari inspires the listener to contemplate their inner self and seek harmony with the divine presence.

Conclusion

Asavari, along with other ragas, is a testament to the Sikh Gurus’ innovative and transformative use of music to connect with the divine and guide humanity on a path of righteousness. The melodies transcend boundaries, connecting individuals with the universal truths of life, humility, and devotion.