JATHA, derived from Sanskrit yutha, meaning a herd, flock, multitude, troop, band, or host, signifies in the Sikh tradition a band of volunteers coming forth to carry out a specific task, whether in armed combat or peaceful, nonviolent agitation. It is unclear when the term jatha first gained currency, but it was in common use by the first half of the eighteenth century. After the arrest and execution of Banda Singh Bahadur in 1716, the terror unleashed by the Mughal government upon the Sikhs forced them to leave their homes and move about in small bands or jathas, each grouped around a jathedar or leader, who rose to this position due to his daring spirit and capacity to win the confidence of his comrades.

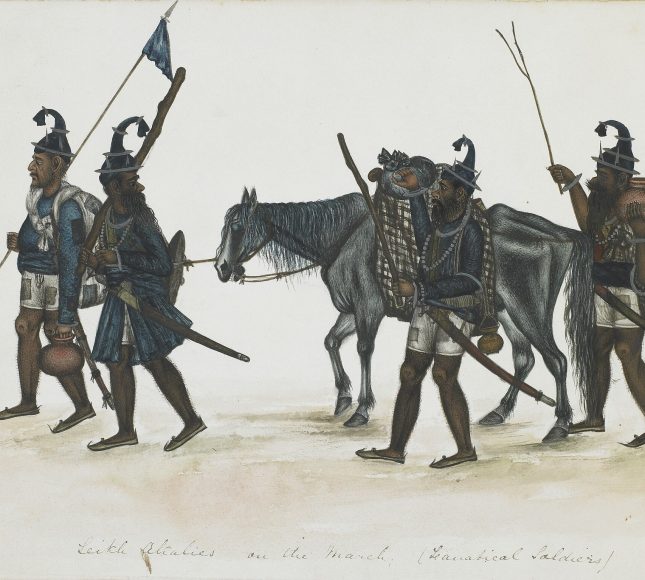

For every able-bodied Sikh who had undergone the vows of the Khalsa, it became necessary to join one or the other jatha to fight against oppression. Besides skill in the use of arms, he had to be a good horseman, as guerrilla warfare, which the Sikhs resorted to against the superior might of the State, required speed and mobility. The weaponry in the beginning ranged from knobbed clubs, spears, and battle axes to bows and arrows and matchlocks. A long sword and a dagger were, of course, carried by every member of the Khalsa.

Some members wore armor but no helmets. During raids on enemy columns and baggage trains, the most valued booty was good horses and matchlocks, so most of the jathas were gradually equipped with firearms. Heavy artillery pieces were not favored as they impeded mobility and speed. However, as Ratan Singh Bhangu notes in Prachin Panth Prakash, the Sikhs carried lighter artillery pieces such as zamburaks (camel swivels) and long-range muskets, called janjails. Usually, each jatha had to fend for itself, but it was necessary to coordinate its activities with those of others and operate under an overall plan.

The diverse jathas voluntarily accepted the control of Sarbat Khalsa, the assembly of all Sikh jathas held at Amritsar on occasions such as Baisakhi and Divali, when plans of action were formulated in the form of gurmatas or resolutions adopted in the presence of the Guru Granth Sahib. The brief respite provided by a temporary détente with the government during 1733–35 enabled the Sikh jathas to assemble and stay in strength at Amritsar with immunity. Nawab Kapur Singh, their chosen leader, organized the entire force into two dals, i.e., branches: the Buddha Dal (army of the old) and the Taruna Dal (army of the young). The Taruna Dal was further divided into five jathas, each with its own flag.

With the end of the détente and the renewal of State persecution with redoubled vigor, the Sikhs again resorted to smaller, more numerous jathas. The need for coordination forced them to regroup themselves on Divali of 1745 into 25 jathas, but the number multiplied again. `Ali ud-Din Mufti, in his Ibrat Namah, mentions 65 jathas. They were finally reorganized on the Baisakhi of 1748 into 11 misls under the overall command of Jassa Singh Ahluwalia. The entire Sikh fighting force was named Dal Khalsa Ji. The misls were large bodies of mounted warriors and might have been divided into subunits, but the terms jatha and jathedar gradually fell into disuse.

The leaders of the misls and commanders of Dal Khalsa preferred to be called sardars, a term borrowed from the Afghan invaders under Ahmad Shah Durrani. The establishment of monarchy under Maharaja Ranjit Singh put an end to older institutions like jatha, misl, Dal Khalsa, Sarbat Khalsa, and gurmata. During the religious revival of the late nineteenth century, Sikh reformers adopted the term Khalsa Diwan for their central bodies and Singh Sabha for local branches, as well as for the entire movement. The term jatha was generally restricted to bands of preachers and choirs, a connotation still in vogue. It was during the Gurdwara Reform movement of the early twentieth century that dal and jatha reappeared.

The apex body of Sikh agitators for political action for the liberation of their shrines from the mahants, the effete priestly class, came to be named the Shiromani Akali Dal, and its locally organized branches, Akali Jathas. During subsequent morchas (peaceful agitations) organized by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee—a body later recognized under the Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925—and by the Shiromani Akali Dal, which emerged as the major political party of the Sikhs, each band of volunteers advancing demands or defying government orders was called a jatha. This use of the term is still prevalent.

References:

- Bhangu, Ratan Singh, Prachin Panth Prakash, Amritsar, 1914.

- Ganda Singh, Sardar Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, Patiala, 1969.

- Forster, George, A Journey from Bengal to England, 2 vols., London, 1798.

- Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Vol. 1, Princeton, 1963.

- Bhagat Singh, Sikh Polity in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Delhi, 1978.

- Gandhi, Surjit Singh, Struggle of the Sikhs for Sovereignty, Delhi, 1980.

- Fauja Singh, Military System of the Sikhs

roop, band or host, signifies in the Sikh tradition a band of volunteers coming forth to carry out a specific task, be it armed combat or a peaceful and nonviolent agitation. It is not clear when the term jathd first gained currency, but it was in common use by the first half of the eighteenth century. After the arrest and execution of Banda Singh Bahadur in 1716, the terror let loose by the Mughal government upon the Sikhs forced them to leave their homes and hearths and move about in small bands or jathds, each grouped around ajatheddror leader who came to occupy this position on account of his daring spirit and capacity to win the confidence of his comrades.

For every able bodied Sikh who had undergone the vows of the Khalsa, it became necessary to join one or the other jathd to fight against the oppressors. Besides skill in the use of arms, he had to be a good horseman, because in guerilla warfare, such as the Sikhs had to resort to against the superior might of the State, speed and mobility were of paramount importance. The weaponry, in the beginning, ranged from knobbed clubs, spears and battle axes to bow and arrows and matchlocks. A long sword and a dagger were of course carried by every member of the Khalsa.

Some of them wore armour, but no helmets. During raids on enemy columns and baggage trains, the booty most valued was good horses and matchlocks so that most of the jathds were gradually equipped with firearms. Heavy artillery pieces were not favoured, as they impeded mobility and speed. However, as Ratan Singh Bharigu, Prachin Panth Prakash, says, they did carry lighter pieces such as zambiiraks or camel swivels and long range muskets, called janjails. Usually, each jathd had to fend for itself; yet it was necessary to coordinate its activities with those of others and operate under an overall plan.

The diverse jathds voluntarily accepted the control of Sarbatt Khalsa, the assembly of all the Sikh jathds at Amritsar on the occasions of Baisakhi and Divali when plans of action were formulated in the form of gurmafdsor resolutions adopted in the presence of Guru Granth Sahib. The brief respite provided by a temporary detente with the government during 1733-35 enabled the Sk} jathds to assemble and stay in strength at Amritsar with immunity. Nawab Kapur Singh, their chosen leader, knit the entire force into two dais, i.e. branches or sections the Buddha Dal (army of the old) and Taruna Dal (army of the young). Taruna Dal was further divided into five jathds each with its own flag.

With the end of the detente and the renewal of State persecution with redoubled vigour, the Sikhs had again recourse to smaller and more numerous jathds. Need for coordination forced them again to regroup themselves on the Divali of 1745 into 25 jathds, but the number multiplied again. `All udDIn Mufti, `Ibrat Ndmah, mentions 65 jathds. They were finally reorganised on the Baisakhi of 1748 into 11 misis, under the overall command of Jassa Singh AhluvalTa. The entire fighting force of the Sikhs was named Dal Khalsa Ji. The misis owere large bodies of mounted warriors and might have been divided into subunits, but the terms jathd an djatheddr gradually fell into disuse.

The leaders of misis and J/VI ruKA the Dal Khalsa preferred to be called sarddrs, a term borrowed from the Afghan invaders under Ahmad Shah Durranl. The establishment of monarchy under Maharaja Ranjit Singh put an end to all these older institutions jathd, misi, Dal Khalsa, Sarbatt Khalsa and gurmatd. During the religious revival of the later nineteenth century, the Sikh reformers adopted the term Khalsa Diwan for their central bodies and Singh Sabha for the local branches as well as for the entire movement. The term jathd was generally restricted to bands of preachers and choirs, a connotation still in vogue. It was during the Gurdwara Reform movement of the early twentieth century that dal and jathd reappeared.

The apex body of Sikh agitators for political action for the liberation of their shrines from the mahants, the effete priestly class, came to be named the Shiromam Akali Dal and its locally organized branches Akali Jathas. During the subsequent morchdsor peaceful agitations organized by the Shiromam Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, a body that later got statutory recognition under the Sikh Gurdwaras Act, 1925, and by the ShiromanT Akali Dal, which emerged as the major political party of the Sikhs, each band of volunteers going forward to press a demand or to defy an unjust fiat of the government, was called a jathd. This use of the term is still prevalent.

References :

1. Bharigii, Ratan Singh, Prachm Panth Prukdsh. Amritsar, 1914

2. Ganda Singh, Sardar Jassd Singh Ahluvdiid. Paliala, 1969

3. Forsler, George, A Journey from Bengal lo England, 2 vols. London, 1798

4. Khushwant Singli, A History of the Sikhs, vol.1. Princeton, 1963

5. Bhagat Singh, Sikh Polity in the Eighteenth find-Nineteenth Centuries. Delhi, 1978

6. Gandhi, Snrjit Singh, St-niggle of the Sikhs for Sovereignty. Delhi, 1980

7. Fauja Singh, Military System of the Sikhs. Delhi, 1964