MIRIPIRI, compound of two words, both of Perso Arabic origin, adapted into the Sikh tradition to connote the close relationship within it between the temporal and the spiritual. The term represents for the Sikhs a basic principle which has influenced their religious and political thought and governed their societal structure and behaviour. The word mm, derived from Persian mir, itself a contraction of the Arabic amir (lit. commander, governor, lord, prince), signifies temporal power, and pm, from Persian pir (lit. old man, saint, spiritual guide, head of a religious order) stands for spiritual authority.

The origin of the concept of mmpm`is usually associated with Guru Hargobind (1595-1644) who, unlike his five predecessors, adopted a princely style right from the time of his installation in 1606 as the sixth Guru or pro-phetmentor of the Sikhs, when as part of the investiture he wore on his person two swords, one representing mm or political command of the community and the other pin, its spiritual headship. For this reason, he is known as mm pm damdlik, master of piety as well as of power. This correlation between the spiritual and the mundane had in fact been conceptualized in the teachings of the founder of the faith, Guru Nanak (1469-1539) himself.

God is posited by Guru Nanak as the Ultimate Reality.He is the creator, the ultimate ground of all that exists. The man of Guru Nanak being the creation of God, partakes of His Own Light. How does man fulfil himself in this world which, again, is posited as a reality? Not by withdrawal or renunciation, but, as says Guru Nanak in a hymn in the measure Ramkali, by “battling in the open field with one`s mind perfectly in control and with one`s heart poised in love all the lime” (GG,93l). Participation was made the rule.

Thus worldly structures the family, the social and economic systems were brought within the religious domain. Along with the transcendental vision, concern with existential reality was part of Guru Nanak`s intuition.His sacred verse reveals an acute awareness of the ills and errors of contemporary society. Equally telling was his opposition to oppressive State structures. He frankly censured the highhandedness of the kings and the injustices and inequalities which permeated the system.

The community that grew from Guru Nanak`s message had a distinct social entity and, under the succeeding Gurus, it became consolidated into a distinct political entity with features not dissimilar to those of a political state: for instance, its geographical division into manjis or dioceses each under a masand or the Guru`s representative, new towns founded and developed both as religious and commercial centres, and an independent revenue administration for collection of tithes.

The Guru began to be addressed by the devotees as sachehd pdtsdh (true king). Bards Balvand and Satta, contemporaries of Guru Arjan (1563-1606), sing in their hymn preserved in the Guru Granth Sahib the praise of Guru Nanak in kingly terminology. “He constructed the castle of truth on firm foundation, established his kingdom and had the (royal) umbrella unfurled over Lahina`s (Guru Arigad`s) head” (GG, 966). The execution in 1606, of Guru Arjan, Nanak V, under the orders of Emperor Jaharigir, marked the Mughal authority`s response to a growing religious order asserting the principles of freedom of conscience and human justice.

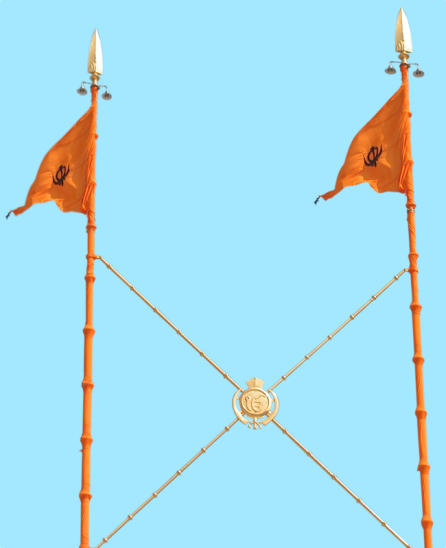

The event led to Guru Arjan`s young successor Guru Hargobind, Nanak VI, formally to adopt the emblems of authority. In front of the holy Harimandar he constructed the Akal Takhl, throne (takht) of the Timeless One {akdt). Here he went through the investiture ceremony for which he put on a warrior`s accoutrement with two swords symbolizing assumption of the spiritual office as well as the control of secular affairs for the conduct of which he specifically used this new seat. He also raised an armed force and asked his followers to bring him presents of horses and weapons.

This was a practical measure undertaken for the defence of the nascent community`s right of freedom of faith and worship against the discriminatory religious policy of the State. To go by the tradition preserved in Sikhan di Bhagat Mala ascribed to Bhai Mani Singh and in Gurbilds Chhevm Pdtshdhi, Guru Arjan himself had encouraged the military training of his son, Hargobind, and other Sikhs. By founding the Akal Takht and introducing soldierly style, Guru Hargobind institutionalized the concept of Miri and Piri. His successors continued to function as temporal as well as spiritual heads of the community although there were no open clashes with the State power as had occurred during his time.

Guru Har Rai, Nanak VII, tried to help the liberal prince Dara Shukoh against his fanatic younger brother, Aurarigzib. To checkmate Emperor Aurarigzib`s policies of religious monolithism, Guru Tegh Bahadur toured extensively in the countryside exhorting the populace to ed fear and stand up boldly to face Oppression. He himself set an example by loosing to give away his life to uphold human freedom and dignity. The blending of Miri and Piri was conmmated by Guru Gobind Singh in the creion of the Khalsa Panth, a republican set), sovereign both religiously and political Ending personal guruship before he died, ` bestowed the stewardship of the commuty on the Khalsa functioning under the lidance of the Divive Word, Guru Granth ihib, in perpetuity.

The popular slogan, Fhe Khalsa shall (ultimately) rule and none [all defy,” is attributed to him; so are the horisms,` `Without state power dharma can3t flourish (and) without dharma all (social brie) gets crushed and trampled upon;” id “No one gifts away power to another; hosoever gets it gets it by his own strength.” Combination of Miri and Piri does not ivisage a theocratic system of government. mong the Sikhs, there is no priestly hierarly. Secondly, as is evidenced by the Khalsa lie in practice, first briefly under Banda [ngh Bahadur and later under the Sikh misis nd Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the form of government established was religiously neutral.

eligion representing Piri did provide moral uidance to the State representing Miri, and ie State provided protection and support qually to the followers of different faiths. .long with the liberation of the individual 3ul, the Sikh faith seeks the betterment of [ie human state as a whole by upholding the alues of freedom of belief and freedom from he oppressive authority, of man over man.

leligious faith is the keeper of human concience and the moral arbiter for guiding nd regulating the exercise of political auhority which must defend and ensure freedom of thought, expression and worship. “his juxtaposition of the moral and secular (bligations of man is the central point of the siikh doctrine of MiriPiri. 10. McLeod, W.H., The Evolution of the Sikh Community. Delhi, 1975 11. Nripinder Singh, The Sikh Moral Tradition. Delhi, 1990

References :

1. Sabadarth Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Amritsar, 1959

2. Gurdas, Bhai, Varan. Amritsar, 1962

3. Mani Singh, Bhai, Sikhan di Bhagat Mala. Amritsar, 1955

4. Sohan Kavi, Gurbilas Chhevin Patshahi. Amritsar, 1968

5. Macauliffe, M. A., The Sikh Religion. Oxford, 1909

6. Banerjee, Indubhusan, Evolution of the Khalsa. Calcutta, 1936

7. Sher Singh, The Philosophy of Sikhism. Lahore, 1944

8. Teja Singh, Sikhism: Its Ideals and Institutions. Bombay, 1937

9. Kapur Singh, Parasaraprasna or the Baisakhi of Guru Gobind Singh. Jalandhar, 1959

Miri Piri: The Dual Aspects of Spirituality and Sovereignty in Sikhism

Miri Piri, a fundamental principle in Sikhism, signifies the harmonious integration of spirituality (Piri) and temporal sovereignty (Miri). This concept was formally introduced by Guru Hargobind, the sixth Sikh Guru, who advocated that a balanced life requires attention to both spiritual pursuits and worldly responsibilities. The idea embodies the Sikh belief that spiritual strength and moral authority must translate into active engagement with society, governance, and justice.

Historical Context

The concept of Miri Piri emerged in response to the challenges faced by Sikhs during Guru Hargobind’s time. Following the martyrdom of his father, Guru Arjan, Guru Hargobind realized the need to equip the Sikh community to defend themselves against oppression and injustice. He donned two swords—one symbolizing Miri (temporal authority) and the other symbolizing Piri (spiritual leadership)—to represent the dual responsibility of a Sikh to uphold spiritual integrity while addressing worldly matters.

Guru Hargobind constructed the Akal Takht (the Throne of the Timeless One) in 1606, adjacent to the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple), to serve as the center of Miri Piri. This physical manifestation of the concept underscored the interconnectedness of spirituality and governance, illustrating that a Sikh must contribute to society while remaining grounded in spiritual values.

Philosophical Significance

Miri Piri reflects the Sikh ideal of a balanced life. It emphasizes that spirituality is not a passive or isolated pursuit; rather, it should empower individuals to actively engage with the world and uphold justice, equality, and righteousness. The two realms—spiritual and temporal—are seen as interdependent, with spirituality providing the ethical framework for worldly leadership and governance.

This principle also challenges the notion of renunciation or withdrawal from society. Sikhs are encouraged to embrace their responsibilities in the world while maintaining a connection with Waheguru (God). By embodying Miri Piri, a Sikh finds strength in faith and uses that strength to protect others, promote equality, and work toward the betterment of society.

Modern Relevance

The philosophy of Miri Piri remains highly relevant today. It serves as a reminder that spirituality should inspire action, and that true leadership is guided by compassion, humility, and moral integrity. For individuals and communities, Miri Piri provides a framework for addressing social issues, advocating for justice, and fostering harmony while staying rooted in spiritual values.

In contemporary Sikh practices, the Akal Takht continues to symbolize Miri Piri, serving as a place where temporal decisions are made in alignment with Sikh principles. Sikhs worldwide draw inspiration from this concept, applying its teachings to leadership, activism, and service.

Conclusion

Miri Piri encapsulates the Sikh philosophy of living a balanced and purposeful life. It teaches that spirituality is the foundation for ethical governance and action, while worldly engagement reinforces spiritual growth. By integrating Miri and Piri, Sikhs are empowered to lead lives of courage, compassion, and commitment to justice, making this principle a cornerstone of Sikh identity and practice.