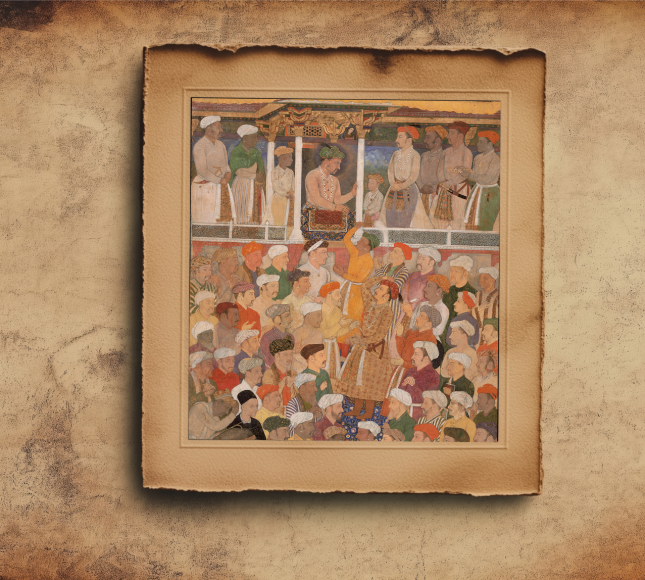

Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri is one of the several titles under which the autobiographical writing of the Mughal Emperor, Jahangir (1605-27), is available, the common and generally accepted ones being Tuzuk-i-Jahangir, Waqi’at-i-Jahangir, and Jahangir Namah. The Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri based on the edited text of Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan of Aligarh is embodied in two volumes translated by Alexander Rogers, revised, collated, and corrected by Henry Beveridge with the help of several manuscripts from the India Office Library, British Library, Royal Asiatic Society, and other sources. The first volume covers the first twelve years, while the second deals with the thirteenth to the nineteenth year of the reign. The material pertaining to the first twelve of the twenty-two regnal years, written by the Emperor in his own hand, is followed by events and occurrences of the next three years which were recorded under imperial orders by Mu’tamad Khan in his Iqbalnamah, at the end of which he omitted the royal name. Muhammad Hadi continued the account, adding a preface and notes up to the death of the Emperor. Jahangir had the memoirs of the first twelve years of his reign bound in a volume, of which several copies were made and distributed. The Iqbalnamah and the account and notes by Muhammad Hadi followed in due course of time. The work is in chaste Persian which Jahangir knew as well as he did his ancestral Chughtai Turki, the language used by his great-grandfather, Babur, in his memoirs, Tuzuk-i-Baburi. Jahangir, pleasure-loving, impulsive, capricious, unpredictable, and at times ruthless, was a lover of nature, art, and literature, and had an acute power of observation to which his memoirs bear witness. But he lacked the religious catholicity of his father and leaned more towards the orthodox section among his courtiers. This coterie was under the influence of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1569-1624), leader of the Naqshbandi order of Sufis, whose one aim was to have Emperor Akbar’s policy of religious tolerance and eclecticism reversed. The Sikh order was the first to bear the brunt of Jahangir’s intolerance. As the Emperor records in the Tuzuk, he was aware of the popularity of Guru Arjan (1563-1606) among Hindus and Muslims, and had long desired to put an end to the new creed. The meeting of his rebel son, Khusrau, with Guru Arjan gave him a ready excuse. He had the Guru arrested and tortured to death. Following is a translation of an entry made by the Emperor in his Tuzuk on 22 Safar 1015 AH (19 June 1606), 20 days after the execution of Guru Arjan:

“At Goindval, situated along the bank of the River Beas, was a Hindu (sic) named Arjun, who went about as a religious teacher. A large number of simple-minded Hindus, even stupid and ignorant Muslims, were attracted to his way, and his reputation as a teacher of religion got widespread. They called him Guru. Followers and practitioners of superstition from all directions turned towards him and reposed great faith in him. This commerce had been going on for three or four generations. For a long time it had been in my mind that this false business should be brought to an end or he [Guru Arjan] should be brought within the fold of Islam, until the time Khusrau came that way… Khusrau made a stop at his place. He had an audience [with Khusrau], supplied certain provisions to him, and made on his forehead a saffron mark with his finger called qashqa [i.e. tilak] considered among the Hindus an auspicious sign. As this matter reached the royal ear and as I fully understood his falsehood, I commanded that he be brought before me. I made over his houses, lands and his children to Murtaza Khan and ordered that his property be confiscated. I ordered his execution according to State policy and law.”

As for Khusrau’s visit to Guru Arjan, an old Sikh chronicle, Mahima Prakash, records that “he (Khusrau) was in serious trouble. The Guru extended to him the hospitality of Guru ka Langar. Spending the night there, he resumed his journey.” There was no other help provided to the fugitive prince.

References:

- Beveridge, Henry, ed., The Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri. Delhi, 1968