YOGA Derived from the Sanskrit root yuj (equivalent to Latin jugum, Gothic juk, German jock), yoga shares its meaning with yoke in English. Yoga refers to the yoking or harnessing of the mind to cultivate paravidya or higher knowledge—the result of psychical and physical processes employed to discover man’s supreme inner essence through samadhi. Samadhi being the ultimate stage, various ascetic practices precede it, found in different types of yoga such as Mantra, Hatha, Laya, and Rajyoga.

Rajyoga Rajyoga, or eight-limbed (ashtang) yoga, is based on Patanjali’s Yogasutras, rooted in the metaphysics of the Sankhya system, sometimes regarded as a pre-Aryan postulation. Yoga practices existed before Patanjali, who organized scattered sutras into the treatise later known as Yogasutras, an authoritative critique on yoga. It remains unclear whether this Patanjali is the same person as the grammarian Patanjali.

Yoga has been defined as the silencing of mental ripples: yoga chittvrtti nirodha. The Bhagavadgita discusses aspects of yoga such as karmayoga, jnanayoga, and bhaktiyoga. Aurobindo envisioned spiritual advancement through yoga, calling his approach “integral yoga,” focusing on a complete transformation of being.

Classifications Equanimity of mind can be achieved through various methods. Yoga has been classified into four major types: Mantrayoga, Hathayoga, Layayoga, and Rajyoga. These categories overlap and are interconnected. Among them, Hathayoga is the most popularly known. It advocates controlling the body’s systems to master the subtle body.

- Mantrayoga: In this form, creation is considered namrupatmak (filled with names and forms). Through mantras, the yogi deduces creation into one idea, ultimately reaching the universe’s final cause. Mantrayoga influences Hindu scripture and idol worship.

- Layayoga: This method identifies pressure points (chakras), using the kundalini at the base (lotus) to reach the sahasrar, located in the skull’s uppermost region. The merging of Sakti with Siva in the skull leads to Mahalaya samadhi.

- Hathayoga: Gross-body exercises cleanse the subtle body of worldly passions, bringing it face-to-face with supreme reality. Practices include six actions (sat karmas), asana, mudra, pratyahara, pranayama, dhyana, and samadhi.

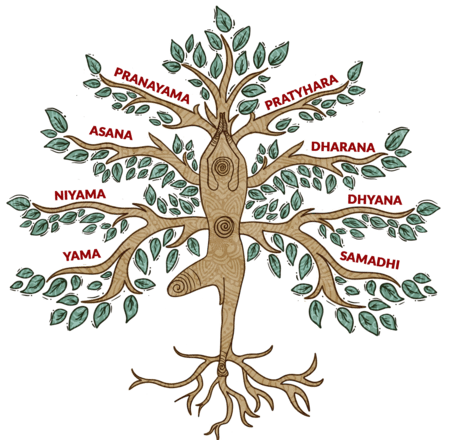

- Rajyoga: Focuses on mental discipline through eight limbs: yama (don’ts), niyama (do’s), asana (posture), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (sense withdrawal), dhyana (contemplation), dharana (meditation), and samadhi (superconscious absorption).

Yoga promotes a diseaseless body, enabling physical discipline and penances. Authoritative texts include Goraksa Satak (Gorakhnath), Hathayoga Pradipika (Svatmarama), Gheranda Samhita (Gheranda), and Siva Samhita (a tantric text).

Yoga and Sikhism Sikhism rejects traditional yoga practices, emphasizing intense love and reverence for God instead. Sikh Gurus, like true karmayogis, lived active lives detached from worldly attachments. Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh critiqued distortions of yoga prevalent in their time, which reduced it to earning sidhis and intimidating followers.

While Sikh Gurus used yoga terminology in their verses, they advocated nam simaran (remembrance and praise of God) over self-mortification. Sikh teachings aim at mankind’s welfare. Guru Nanak emphasized the futility of six-fold actions, Vedas, Smrti, yogic exercises, and pilgrimages without love for God (GG, 11^4). Guru Gobind Singh reiterated this in Akal Ustati (Dasam Granth).

Gurbani acknowledges the body’s chakras and the upside-down lotus, which blooms through God remembrance (GG, 108). According to Gurus, man must become gurmukh to rise above the nine outlets and hear the Word’s unstruck sound. Ego-conquest and devotion are celebrated, while nidhis and sidhis are rejected.

Yoga mysticism lacks social and cultural roots, whereas Sikhism is firmly embedded in society and worldly responsibility. A Sikh mystic pursues spiritual perfection to serve Truth and God while testifying to His existence, grace, and love.

References:

- Jodh Singh, The Religious Philosophy of Guru Nanak, Varanasi, 1983

- Briggs, G.W., Gorakhnath and the Kanphata Yogis, Varanasi, 1973

- Barthwal, P.O., Gorakh Bani, Prayag, 1960

- Dwivedi, Hazari Prasad, Nath Sampradaya, Varanasi, 1966

- Svatmarama, Hathayoga Pradipika